The

book "Valzergues fluorite mine"

![]() E.

Guillou-Gotkovsky

E.

Guillou-Gotkovsky

![]() Comments

Comments

![]() How

to get the book

How

to get the book

The Trepca mine

The Trepca mine has yielded to museums and to collectors of all the world exceptional specimen of various minerals, particularly vivianite, ludlamite, jamesonite, pyrrhotite, arsenopyrite, dolomite et more commonly very beautiful sphalerites (marmatite). It is a giant weighing 60 millions tons ore containing 5 millions tons lead and zinc metal. Despite no fluorite has been identified there yet, the sad fate which has fallen on this famous deposit since 1990 and since the Kosovo war fully justifies one page of the website be devoted to it.

|

|

| Serpentines

and tertiary basin of the Ibar valley Photos Jean Feraud © 2004 | |

1)

A few words of History

A few more comments

than usual are necessary to understand the ethnologic-political-economical imbroglio

which surrounds the mine. However it will be more cautious having not too much

faith to the various passionate Internet sites which are proliferating, furthermore

as each element given on Spathfluor.com without deep verification by us may become

a piece of the claiming puzzle, manipulated by one side or the other for its profit,

would it be without or not without reason. This History of the mine and of its

region is even so exciting.

Gold and silver mining by the Romans is proved by texts and by huge slags heaps

for numerous ore deposits in the Balkans, as in the North-West of Trepca (Srebrenica)

as in the North (Rudnik, Socanica) and in the South (Gracanica). Afterwards, the

region is influenced by ethnological, colonization and or/political successive

events particularly byzantine, bulgarian, serbian, turkish and albanian population

streams which explain the cultural mixing, the revenge spirits, and (partly) help

to understand the current imbroglio.

The

Middle Ages

For Trepca, the first phase of extraction

proven to date is medieval (for silver, lead and iron) ; it begins in 1303 and

the activity is intense. This productivity answers to the need of the successive

lords and of their serbian suzerain, for their military activities ; it is it

which finances the building of fortresses all along the Ibar valley against the

ottoman threat. Saxons miners seem to have been involved. On June 15th 1389 occurs

at a dozen kilometres South from Trep_a the famous battle of the Blackbirds Field

: the serbian army is overwhelmed by the Turks in the Kosovo plain. But the historians

do not notice any interruption in the mine production, because it seems that a

kind of protectorate is settled at first, and that the seignory to which the mine

belongs (Shala e Bajgorës) keeps some independence (one knows that a turkish

kadi was instated at the Gluhavica mine near Novi Pazar). In the mines, the turkish

supervisors disregard the representatives of the serbian owners and endeavour

to prevent silver exports. The extraction is first disrupted because of the anarchic

management and of the escape of the qualified labourers ; but from 1455 it is

very well taken in hands again by the turkish administration, date of the total

conquest of Turks over the last provinces remained independent. They improve the

serbian mining code and actively exploit Trep_a and the other mines in order to

feed their currency and weapon factories, till 1685. That year is the begin of

a fast decline of all the Balkans mines, quickly paralysing as well the famous

gold, silver and lead mines of Novo Brdo.

Selection

Trust

Trep_a is being talked about again in 1925 only, when

a big exploration programme is carried out by the British company Selection Trust

which assesses the huge potential of the ore deposit and which launches in 1927

in London a « Trep_a Mines Limited » subsidiary ; that one opens in

1930 the « Stan Trg » mine, on the spot of the ancient medieval open

pit. This name is a misprint, by the British administration of the mine, from

the toponym Stari Trg which means « old place », « old market

». Did the typist who copied the instituting documents of the mining claim

not correctly read the « ri » of the handwritten note of her boss,

and did she typed by mistake an « n » ? Amazingly, the obvious misprint

will not be corrected in any later document, not in any mine plan, not in the

famous publication edited by C.B. Forgan in the international geological congress

of 1948. Either the mine owners did not have a great knowledge of the local language,

either their representatives on the spot have thought more cautious to keep silent

and not to create a legal flaw in the official certificates (which might have

made null and void the mine property or taken the risk to disturb the share holders

!). The geologist F. Schumacher less anxious (since Tito had just confiscated

the mining rights from Selection Trust) will rectify the correct name in his memoir

of 1950.

The mine rapidly reaches a blasting rate of 600 to 700,000 tpy. From 1930 to 1940,

it yields 5.7 Mt run-of-mine ore producing in the flotation plant on the spot

625,000 t lead concentrates, 685,000 t zinc concentrates, 444,000 t pyrite concentrates

and a mixed concentrate of lead and copper. A lead smelter is built at Zvecan

in 1940. During the world war, Trep_a is exploited by a company owned by Goering

himself and it produces in particular batteries for the U-Boote ! After the war,

the mine and the smelter are nationalized as a whole by Tito.

| Rudarsko Metalurski Hemijski Kombinat Olova i Cinka Trepca

|  |

The

fall

This complex which employed 20,000 people and produced

70 % of the mineral industry income of whole Yougoslavia (thus including Slovenia)

progressively collapsed during the last fifteen years, first because of installations

outdating, neglect of housekeping, lack of maintenance, lack of repair and reinvestment,

absence of control over production and grades, robbery of equipments and sometimes

of workshops. Privatization attempts remained without great follow-up. The fall

increased from 1990 with the cancellation by Belgrade of Kosovo autonomy, the

increasing ethno-political tension and the leave of the workers of albanian origin.

During the Kosovo war which followed 1998, Trep_a and Kosovska-Mitrovica where

the population was very mixed were among the most grimly contested goals ; it

was even rumoured that hundreds of kosovar bodies would have been burnt in the

lead smelter furnace (but the investigation of the French police did not find

any proof of that).

The arrival of KFOR and the separation of the belligerents

of both sides in June 1999 led to an outburst of the mining complex. The northern

mines remain exploited by the Serbs. The southern mines which had been drowned

were taken in hands again by the workers of albanian origin but those ones could

not reset them in production yet. In the centre, KFOR had first promoted the resumption

of Trep_a and Mitrovica production. But a French-Danish environmental appraisal

of the sites revealed such an accumulation of polluting substances around the

smelters that the civil administrator Bernard Kouchner ordered by august 2000

the operations be stopped immediately. Since then Trep_a is in greatest part flooded,

it cannot be visited and its two smelters are inactive. There are claims from

various sides concerning the legal ownership of the mining rights and even a rumour

according to which the British would have demanded an indemnification for the

former nationalization by Tito.

To crown it all, on September 18th 1999,

the mineralogical museum of the mine, where jealously guarded treasures had been

accumulated since 1966, was plundered by thieves benefiting from the confusion.

There is no doubt that (like for the Bagdad archaeological museum) the stolen

pieces have disappeared for ever in the cellars of some unscrupulous silent partners

behind. In a website, it was reported that professor Milan Jaksic of the School

of Mines on the spot had informed that the most invaluable vivianite specimen

of the museum had disappeared, as well as more than 1,500 of the crystals collected

inside the mine since 1927, and 150 specimens which had been given by 30 countries

all over the world.

Let all the museums in the world be on the alert about any attempt of resale

by the receivers.

By

the way, the small collectors will be amazed… those who retain the memory

of the constant police close watch over the mine in the 70’s, which nearly

cast a « lead » screed over any possibility to take a nice sample

out the mine shaft and furthermore to buy a single crystal in the village !

Fortunately, good hopes for a resumption of the mine are now permitted. The United

Mission for Kosovo (UNMIK) which rules this province for the time being, has launched

with the approval of all parties an important programme of technical and economical

appraisal for the resurgence of production in all the industrial sites of the

complex. This programme was subcontracted in august 2000 to the ITT consortium

(Interim Team for Trepca) which is composed of the American Morrison & Knudsen-Washington

Group, Boliden Contech, and TEC Ingénierie, a French society of the Eramet

group.

|

|

|

|

Blende,

Rhodochrosite, Arsenopyrite and Calcite

|

Blende

marmatite Edges of crystals : 3 cm Coll. Jean Feraud |

Pseudomorphosis

pyrrhotite-marcasite, calcite Coll. Jean Feraud |

2)

Geology

The

geology of the mine is very attractive. It may well be not yet fully assessed,

furthermore because since the very fine studies of the Selection Trust geologist

C.B. Forgan (supplemented by F. Schumacher in 1950), no comprehensive, detailed,

well illustrated study of this giant deposit has been practically « published

». In between, however, the extent of the mine acknowledged along the dip

has doubled ! All the publications issued either are interpreting synthesis of

the ore deposit and of the whole mineralized belt (S. Jankovi_), or short accounts

or guide-books of a congress visit, without detailed illustrations, or detailed

publications devoted to a particular topic, such as the stratigraphic datings

by Kandic and coll. (1973) boldly interpreted by Ivo Strucl (1981).

|

A

trap for 60 Mt ore

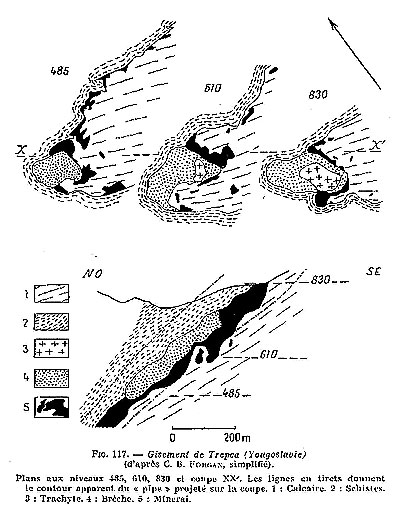

Within the Dinarides alpine belt, the mine

is located in the Vardar zone, a nappe of folded and over-ridden units comprising

a paleozoic basement, a jurassic sedimentary cover and overthrusted cretaceous

ophiolites, intruded during the Tertiary by post-tectonic magmas (granodiorite

and intrusive dacitic-andesitic lavas). The ore deposit is interlayered as a manto

and as skarns within a sedimentary pile (the Stari Trg Series), below a thick

layer of volcanic tuffs (ignimbrite ?) of tertiary age. More precisely, within

the Stari Trg Series the ore bodies are intercalated between (at the bottom) thick

marmorised limestones and (at the top) thick schists : a stratigraphic contact

which is from place to place occupied by an intercalated layer of quartzite. This

contact is folded in an anticlinal hinge, the NW-SE axis of which has a pitch

of 40° towards the NW. The whole structure looks a little more complicated

when one’s knows that a volcanic chimney (an explosion breccia of oval 100

x 200 m section with a core made of a pipe of trachyte or dacite) was intruded

all along the crest of this anticlinal hinge, precisely within the interface between

the schists and the limestones. It is this pipe which (fundamentally) controls

the presence of the mineralisation. The ore has wormed its way into or nearly

only into the interface schist/limestone on one side of the volcanic pipe and

on the other. It reaches 30 up to 60 m thick on average. There are a few discordant

oreshoots as well. There are also other smaller prospects of the same type as

Stari Trg in the neighbourhood of the mine.

(that’s all folk, to simplify…).

The ascent of the miocene granodiorite of Mounts Kopaonik was probably not without

any metallogenic influence as well. The magma is responsible of the formation

of skarns with garnet, pyroxene, amphibole and magnetite in the ore bodies, and

of the presence of veins of dacite or dolerite within the host rocks. Within those,

the mineralizing hydrothermalism was accompanied by propylitization-sericitization,

silicification, carbonatization, pyritization and kaolinitization.

The genesis of the giant is simple !

The

collector enjoys that, in the alpine epoch, waters have percolated within the

rocks, have then warmed and been loaded with metals at the contact of the magmatic

masses and fluids which were rising from the melting zone of the tectonic plates

below. These waters were then blocked during their ascent by the waterproof screen-like

roof made by the thick schists.

Because of their temperature and of their

aggressive chemical properties, they then dug by simple dissolution within the

limestones, below this screen, vast cavities. The crystallisation of salts in

solution has gradually coated these cavities by concretions and, if a remaining

vacuum permitted it, by gigantic crystals. From that point of view, the metallogenetic

classification of Trepca as given in the GIS databases on the Web is not complete

: it should be spoken as well of « karst » (even if it was at hot

temperatures) and of « ore deposit under unconformity ».

Is

thus the genesis of our Trepca giant fully assessed ? No. We have delineated the

conditions of “deposition” of the ore (dissolution of karstic caves,

oreshoots using the wonderful hydrogeological trap of the area, skarn controlled

by a volcanic pipe). We have determined the “transportation” of the

ore (hydrothermal solutions rising through a complex plumbing system). But for

the “source of the elements” (which is the beginning of all the story),

we have given a vague origin : the magma. Since it is well known that there are

usually volcanogenic massive sulphides deposits generated within such ophiolitic

belts, could one have existed in depth, which would have yielded the metals in

such quantities ? Let’s hope that the experts of the universities working

now nearby will answer to the remaining question marks in the near future…

And

if… ?

It would be simplistic to pass in silence over the

debate about the polarity of the mineralized sequence. In fact, nobody exactly

knows if the schists are older than the limestones, or the opposite. Previously

the geologists assumed that the Stari Trg Series sedimentary sequence was Silurian-Ordovician

but Yougoslavian geologists found fossils (Conodontes) inside (information got

from Aleksandar Topalovi_ in the mine in 1973) which suggests that one part of

the limestones could be triassic. The presumed bottom of the sequence may well

be thus the top !

How to make sense of this overthrusted and distorted zone

between the african plate and the euro-asian plate ? Instead of an anticline,

the purists will therefore speak cautiously of antiform. And the fans of global

metallogenesis will dream (following Ivo _trucl) at the consequence that, if the

limestones are triassic, then Trepca is a milestone (as near as make no difference,

except the role of tertiary magmas) of the same mineralizing processes which generated

all along the Alps the stratabound lead-zinc ore deposits of Mezica, Raibl, Salafossa,

La Plagne, Largentière, Les Malines etc. (here we’re day dreaming

but dreams make science progress).

Inside the collectors ear we will « instil » as well that none of

the stalactites of carbonates mineralized in sulphides that were found in Trepca

till now showed any axial canal for the drops of water which fall down from the

ceiling of the caves. That means that the karst was totally flooded and that the

vugs (the caves) were not coated by sulphides in the open air but under a water

table (a more or less mineralized water). So, please, inform us of any axial canal

that you would come to collect ! it would be a scoop.

3)

Mineralogy

The Mindat.org website has listed 30 valid mineral species. The specialized publications (in serbo-croat) that were compiled in Mari (1979) indicate as well, beside the usual minerals of oxidation present, a few other remarkable species. Altogether more than 60 minerals are thus listed to date (by alphabetical order) :

| Actinolite Anglesite Ankerite Aragonite Arsenopyrite Barite Bismuth Bornite Boulangerite (among which plumosite var.) Bournonite Calcite (among which the manganoan calcite var.) Cerusite Chalcanthite Chalcedony Chalcophanite Chalcopyrite Childrenite Chlorite Coronadite Cosalite Covellite Crandallite Cubanite Diopside Dolomite Enargite Epidote | Falkmanite Galena Garnets Gypsum Hedenbergite Hematite Illite Ilvaïte Indium Jamesonite (among which plumosite) Limonite Löllingite Ludlamite Magnetite Marcasite Melanterite Melnikovite Native gold Psilomelane Pyrargyrite Pyrite Pyrrhotite Quartz Rhodochrosite (among which the Fe-rich var. oligonite) Scheelite Siderite Smithsonite Sphalerite (marmatite var.) Stannite Stibnite Struvite Tennantite Tetrahedrite Thalium Valleriite Vivianite Wollastonite. |

|

|

|

| Plumosite,

rhodochrosite, calcite, arsenopyrite Coll. Jean Feraud |

Sphalerite:

5 cm diam, calcite, dolomie Coll. Jean Feraud |

Galene,

sphalerite (1 cm), arsenopyrite, rhodochrosite, calcite & pyrite -Coll. Jean Feraud |

|

|

|

| Marmatite

7 cm (spinel law twin) Coll. Jean Feraud |

Arsenopyrite,

calcite xx 3 cm Coll. Jean Feraud | Quartz

& calcite 15cm Coll. Jean Feraud |

From a museological viewpoint, many of these minerals are of exceptional quality. Sphalerite marmatite, black, mostly occurs as octahedrons, with striated lustrous faces and sometimes spinel-law twinning. The crystals may reach 7 and exceptionally 10 cm in diameter, but most of them are not more than 2 to 3 cm. They are very generally associated with a calcite crystallization. A recent survey by Slovenian and German scientists showed that the twin planes [111] of sphalerite are depleted in S and enriched in O, Mn, Fe and Cu. An excess in copper generates the crystallisation of minute chalcopyrite crystals along this plane. Pyrrhotite is remarkable by its crystals of hexagonal tabular habitus reaching up to 16 cm diameter, particularly if it is not pseudomorphosed in pyrite-marcasite. It is rather rarely pseudomorphosed into galena. Galena occurs as cubes and octahedrons reaching 5 cm in edge ; it has a particular habitus characterized by corroded, eroded, melted-like faces and growing hillock structures (“flowing galena” of the german authors). Arsenopyrite often occurs as very beautiful aggregates of parallel tabular crystals, or as short prisms with [012] flat diamond-shaped faces ; the crystals are up to 5 cm in edge, but most of the collectors content themselves with a few millimetres ! Vivianite does not reach the sizes of Cameroon specimens but it forms sometimes flat prisms up to 7 and even a dozen centimetres long and 2 cm thick. It is of a very beautiful deep green. Ludlamite, apple-green, more rare, is much more appreciated. Boulangerite occurs as downy masses of very fine, fibrous, entangled crystals called plumosite ; a few needles reach 30 cm in length. Jamesonite is more rare ; the mine museum exposed a specimen where the crystals reached 4 cm long and 1.5 cm diameter. Chalcopyrite and pyrite are more banal.

It is the combination of the sulphides (with their beautiful metallic shine) with

the lustrous or pearly crystals of quartz, dolomite and calcite, and with the

pink ones of rhodochrosite, which confers to the specimens coming from Trep_a

all their magic for the collectors. Dolomite sometimes forms beautiful rhombohedrons

up to several kg in weight and 10 cm edge, associated with quartz needles. Quartz

(white to hyaline) sometimes is sceptre shaped and up to 7 cm long.

From time to time, the scientists discover new species for Trep_a ; in 1995, it

was the turn of a phosphate very rare in the world, childrenite (accompanied by

its alteration mineral crandallite). The mineral forms free-standing doubly-terminated

crystals up to 1 cm in diameter, in drusy aggregates associated with the (Mn,

Fe) carbonates. It is pale yellow, dimly white in the core and more transparent

and brown at the corners. The occurrence of boulangerite inclusions inside childrenite

suggests that childrenite was formed under low-temperature hydrothermal conditions.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Blende marmatite (xx from 1 to 2 cm), galena and rhodochrosite Coll. Jean Feraud courtesy of Franz Huber | ||

4)

Exploitation

Starting from the medieval open pit at the 935 m mark, the exploitation has deepened underground by the cut and fill method. The access to the stopes was previously done by a few adits at the top of the mine (at heights of 865, 830, 795 and 760 m), then, in order to exploit the downdip, a shaft was dug which gives access the other successive levels. The deeper levels are reached by inclines from the bottom of the shaft. The total vertical extent of the mine was 800 m at the time it has stopped. From the shaft at the 605 mark starts a dewatering adit 2.5 km long towards the SW. At each level the mining stopes are elongated horizontally on both sides of the volcanic pipe intersection, along the two sides of the antiform, over a total length of about 500 m towards the NE and 400 m towards the South. Each stope is around 70 m wide and 100 m long.

|

|

|

| Main

head frame | Primary

crusher | Main

entrance |

|

|

|

| ...

in a geode. | Mécanisation

au 1eme niveau | Recette

au 1ème niveau |

|

Jean

Feraud © 2000-2007 |  |

| Stibnite |

Karstic

medley. |

5) Ore beneficiation, production

The total production of Trep_a from 1931 to 1998 is estimated at 34,350,000 t

run-of-mine ore at grades of 6 % Pb, 4 % Zn, 75 g/t Ag and 102 g/t Bi. The ore

was beneficiated in the Prvi Tunel (Tuneli Pare) concentrator (flotation) the

capacity of which was 760,000 tpy. The lead concentrates were brought to the lead

smelter of Zvecan (capacity 80,000 tpy), the zinc ones to the zinc smelter of

Mitrovica (capacity 50,000 tpy) ; there was also a unit for the production of

fertilizers using the sulphuric acid by-product of the hydrometallurgy, and lines

of battery production and battery recycling.

The metal tonnage produced was 2,066,000 t lead, 1,371,000 t zinc, 2,569 t silver

and 4,115 t bismuth. Gold production is estimated at 8.7 t from 1950 to 1985,

i.e. and average of 250 kg per year ; the cadmium production is estimated at 1,655

t from 1968 to 1987. Traces of germanium, gallium, indium, selenium and tellurium

in the run-of-mine ore have been also reported, which were valorized at the level

of the smelters.

6)

And now ?

The

resumption expected by everybody must pass by the preliminary steps of decontaminating

the plants, settling efficient processes and procedures to prevent any new pollution,

and attracting private investors. The programme for updating the plants will be

expensive (the figure of 15 to 30 M USD was rumoured for the whole of the industrial

complex). As concerns the Trep_a mine it seems (according to the first calculations

published on the Web) that the reserves remaining in depth are worth doing all

these efforts. The ITT/UNMIK 2001 report concluded that the tonnages of A+B+C1/C2

categories would be about 29,000,000 t run-of-mine ore at grades varying (according

to the panels considered) from 3.40 to 3.45 % Pb, 2.23 to 2.36% Zn and 74 to 81

g/t Ag, i.e. in metal around 999,000 t Pb, 670,000 t Zn and 2,200 t Ag. This would

yield another 50 years mining if the operation costs and the market permit it

! The goal of the “Trep_a giant” rescue is mobilizing : to revitalize

all this area, to give employments, hope and pride again to the people.

Of course, the small collectors would enjoy the revival of extraction in the nearer future !

7)Recent

or indispensable references

Bancroft

P. (1988) – Mineral museums of eastern Europe. The Mineralogical Record,

vol. 19, n° 1, p. 44-45, 50.

Barral

J.-P. (2001) – Réhabilitation du combinat minier de Trepca au Kosovo.

I.M. Environnement (revue de la Société de l’Industrie Minérale),

n° 12, avril 2001, p. 6-10.

Bermanec

V., Scavnicar S., Zebec V. (1995) – Childrenite and crandallite from the

Stari Trg mine (Trepca), Kosovo : new data. Mineralogy and Petrology 52, p. 197-208.

Dusanic

S., Jovanovic B., Tomovic G., Zirojevic O., Milic D. (1982) – History of

mining in Yougoslavia. In Cuk L. editor, Mining of Yougoslavia, 11th World Mining

Congress, Beograd, p. 119-140.

Féraud

J. (1974) – Trepca (Kosovo), compte rendu de trois visites géologiques

individuelles de la mine effectuées en 1972, 1973 et 1974 . Rapport inédit,

Lab. Géol. appliquée Univ. Paris VI.

Féraud

J. (1979) – La mine « Stari-Trg » (Trepca, Yougoslavie) et ses

richesses minéralogiques. Article publié avec la collaboration de

Mari D. et G. (1979) Minéraux et Fossiles, n° 59-60, p. 19-28.

Forgan

C.B. (1950) – Ore deposits at the Stantrg lead-zinc mine. K. C. Dunham editor,

18th International Geological Congress, London, 1948, Part VII, Symposium of Section

F, p. 290-307.

Hajrizi

F. (2002) – Shala e Bajgorës në vështrimin historik. Site

Internet http://www.trepca.net/histori/020113-shala-bajgores-ne-veshtrimin-historik.htm

ITT

Kosovo consortium LTD (2001) – Trepca orebody assessment. Site Internet UNMIK

http://www.grida.no/enrin/htmls/kosovo/SoE/mining.htm

Kosich

G. (1999) – A look back at Kosovo’s Trepca mines. Copyright Serb World

U.S.A., vol. XV, n° 6, july-august 1999, site Internet http://www.serbworldusa.com/TREPCA.html

Lieber

W. (1973) – Trepca and its minerals. The Mineralogical Record, vol. 4, n°

2, p. 56-61.

Lieber

W. (1975) – Trepca und seine Mineralien. Der Aufschluss, vol. 26, n°

6, p. 225-235.

Monthel

J., Vadala P., Leistel J.M., Cottard F., avec la collaboration de Ilic M., Strumberger

A., Tosovic R., Stepanovic A. (2002) - Mineral deposits and mining districts of

Serbia ; compilation map and GIS databases. Ministry of Mining and Energy of Serbia,

Geoinstitut. Rapport BRGM RC-51448-FR. Site Internet http://giseurope.brgm.fr

Nelles

P. (2003) – The Trepca goal. Trepca Kosovo under UNMIK administration. Site

Internet, novembre 2003, http://www.esiweb.org/pdf/esi_mitrovica_trepca_id_1.pdf

O.S.C.E.

(1999) – Regional overviews of the human rights situation in Kosovo. Site

Internet de l’Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, http://www.osce.org/kosovo/documents/reports/hr/part2/07d-mitrovica.htm

Plachy

J., Smith G. R. (2004) – Zinc/lead in october 2003. USGS Mineral Industry

Surveys, site Internet http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals

Rajavuori

L., Heijlen W. (2001) – Fiche de gisement Trepca. D. Blundell editor, Système

d’information géographique GEODE, hébergé par le BRGM.

Site Internet http://www.gl.rhbnc.ac.uk/geode/ABCD/Trepca.html

Ralph

J. (1993-2004) – Fiche de gisement Trepca. Site internet Mindat.org http://www.mindat.org/loc-3052.html

Schumacher F. (1950) – Die Lagerstätte der Trepca und ihre Umgebung. Izdavacko Preduzece Saveta za Energetiku i Ekstraktivnu Industriju vlade FNRJ, Beograd, 65 p., 14 pl. 2 cartes. Srot V.,

Recnik

A., Scheu Ch., Sturm S., Mirtic B. (2003) – Stacking faults and twin boundaries

in sphalerite crystals from the Trepca mines in Kosovo. American Mineralogist,

vol. 88, p. 1809-1816.

Strucl

I. (1981) – Die schichtgebundenen Blei-Zink-Lagerstätten Jugoslawiens.

Mitt. Österr. Geol. Ges. 74/75, p. 307-322.

Tanjug

Y. (1999) – Priceless crystal collection stolen from Trepca mine museum.

Site Internet http://agitprop.org.au/stopnato/19990919trepca.htm

Bancroft

P. (1988) – Mineral museums of eastern Europe (Trep_a mineralogical museum).

The Mineralogical Record, 19, n° 1, p. 44-45, 50.

Dauti

D. (2002) – Lufta për Trepçën (sipas dokumenteve britanike).

Ed. Institi kosovar për integrime evroatlantike, Prishtinë, 192 p.

Féraud

J. (2004) – La mine de Trep_a/The Trep_a mine. Site Internet (en français)

http://spathfluor.com/_open/open_us/us_op_mines/us_divtrepca.htm et (version en

anglais) http://spathfluor.com/_open/op_fr/op_fr-mines/divtrepca.htm

Féraud

J. (2005) – La mine de Trep_a, son histoire, sa géologie et ses minéraux.

Site Internet de la fédération GEOPOLIS, www.geopolis-fr.com/download/mine-Trepca-mineraux.pdf

et http://www.geopolis-fr.com/art30-mine-trepca-mineraux-mineralogie.html

Féraud

J., Balazuc J., Frima C., Guiollard P.-C., Larderet B., Plakolli S., Schwab J.,

Schwab M., Vendel J. (2005) – Le musée de la mine de Trep_a (Kosovo)

: situation, urgences et perspectives ; impressions d’un voyage exploratoire

11-18 septembre 2005. Rapport indépendant, Comité de soutien pour

le musée de Trep_a, 52 p., résumé anglais

Guillemin

C., Mantienne J. (1989) – En visitant les grandes collections minéralogiques

mondiales (Trep_a, collection de la mine, visite en 1965). Ed. BRGM, p. 245.

Maliqi G. (2001) – Ndërtimi gjeologjik e strukturor i rajonit të Trepçës. Thèse Doctorat Géologie, Université Polytechnique de Tiranës et Faculté de Métallurgie de Kosovska Mitrovica, Université de Prishtinë. Edition Fakulteti i Gjeologjisë dhe Minierave, departamenti i Shkencave të Tokës dega e gjelologijisë, 137 p.

Jean

Féraud

jferaud(at)spathfluor(dot)com